Archaelogical Evidence Supporting the Exodus Account

Using the correct numbers and manuscripts completes an ancient puzzle.

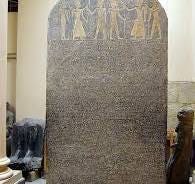

Image: Thutmose III

Academics who take the biblical narrative seriously about the Exodus from Egypt are divided about when it happened. Mention of Rameses (Gen. 47:11; Ex. 12:37; Nu. 33:3) suggests a later date, which raises all kinds of conflicts with history and causes a cloud of doubt about the story. But those mentions may be an indication of when the narrative was put to scroll, not when the events occurred. If you take the Bible dates and numbers seriously, which I did in a very careful study, you come up with an Exodus date of about 1446 BC/BCE (before Christ or before the common era). That makes Amenhotep II, a militant king who often raided Canaan for slaves and concubines, the pharaoh of the Exodus, in which case, by around 1500 BCE Israel was a cohesive ethnic group with an identity worthy of mention along with other well-established groups and states. So although the question may never be settled, we want to know about when Israel became a people that could self-identify as separate from other Canaanite or West Semitic groups. It goes without saying that mention of Israel’s name on a stele (an inscribed stone monument bragging about a king’s conquests) would be just the thing to make the scholars happy.

The traditional first mention of Israel as an ethnic group is on the Merneptah Stele, dated to 1210-1205 BCE. This monument was discovered in 1896 and now resides in the Cairo Museum in Egypt.

Pharaoh Merneptah reigned from 1213 to 1203, the era in which, according to the early dating of the Exodus, the Hebrews (Israelites or Apiru in the Amarna Letters) were already in the Promised Land. In the Bible this era is described in the books of Judges and Ruth. It was a time when, in spite of the Mosaic Law, “every man did that which was right in his own eyes.” Egyptian pharaohs would raid the territory of Canaan, sweeping up extorted protection money from the city leaders, slaves to build their temples, palace singers for entertainment, and beautiful young concubines. Merneptah brags about his latest incursion into Canaan and all the people he devastated. He claimed to have conquered Canaan and Ashkelon and to have wiped out the seed of Israel. At that time, of course, Israel still had no king and no army. All they had were farm implements, so Merneptah’s trained warriors undoubtedly did a lot of harm.

The famous stele got some competition when a German scholar was rooting through the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. He found a slab from an unknown pharaoh that was about a foot and a half feet tall. Like the Merneptah Stele, it was a record of a raid, even mentioning 3 of the locations mentioned in the Merneptah Stele in the same order. The problem is that the name ring that is most likely “Israel” is half chipped away. That aroused debate as to the name, but there are no other credible contenders, and the other two name rings are Canaan and Ashkelon, both close to the territory of Israel. Scholars have dated the monument to around 1400 BCE, about the time of the Conquest of Canaan by the Israelites, who were obviously in the Land when the ancient record was inscribed in stone.

The Bible describes Israel’s battles with various Canaanite cities, but doesn’t mention raids by Egyptian kings. The reason may be that a] the authors of biblical stories prioritized battles that showed God’s protection or lessons that needed to be learned, and b] since Israel was in the land for a long span of years with no central government, there were no recorders or historians to produce a set of yearly annals, so the dates of Egyptian raids were unrecoverable and the harm done was temporary.

I found an interesting Jewish article online that supports the early dating of the Exodus and names the most likely pharaoh. I am in total agreement with what they wrote. It matches archaeological discoveries and with over 300 cuneiform tablets called “the Amarna Letters,” so I’ll let the article speak for itself.

“Our article used what is known as a “high chronology” of Egypt, which has Amenhotep ii reigning circa 1453–1426 b.c.e. This is a relatively popular dating scheme among proponents for Amenhotep ii as pharaoh of the Exodus. But high Egyptian chronology is not the most popular dating scheme among Egyptologists. Instead, it is low chronology, which down-dates these New Kingdom Period pharaohs by several decades.

“This particular dating scheme has risen to overall prominence especially over the past several decades. As such, it is a point of criticism by late-date Exodus proponents against early-date, Amenhotep ii proponents: Against the backdrop of a supposedly settled low chronology, Amenhotep ii cannot be the pharaoh of the early Exodus. Instead, his reign would date to around 1427–1401 b.c.e.—only beginning some two decades after a 1446 b.c.e., early-date Exodus would have occurred.

“Is low chronology the death blow to the Amenhotep ii-as-Exodus-pharaoh theory? Not so fast.

“1 Kings 6:1: MT vs. LXX

“The 1446 b.c.e. Exodus date is derived specifically from a chronological anchor to the building of Solomon’s temple. 1 Kings 6:1 says that this building project began in the 480th year from the Exodus. This temple building date has been rather remarkably pinpointed by different scholars using entirely different means and sources to 967 b.c.e.—a date for which there is virtual unanimity (variant schemes differ by only as much as a year or two). Counting back 479 years (since the building took place in the 480th year) takes us back to 1446 b.c.e. for the Exodus. (Note that this timeframe, and other scriptures in the Bible backing it up, entirely contradicts the late-date Exodus view; late-date proponents have a number of explanations for their dismissal of such passages. See the list of articles at the end for more information.)

“On a low Egyptian chronology system, this 1446 b.c.e. date would put the Exodus well prior to the reign of Amenhotep ii. Instead, it would put it right in the middle of the surging reign of what would arguably become Egypt’s greatest pharaoh: Thutmose iii. (This father of Amenhotep ii, in our scheme, is identified as the primary pharaoh of the oppression.)”

In conclusion, if you take 1 Kings 6:1 seriously from the LXX (the Greek translation called the Septuagint) rather than from the MT (Masoretic Text), then add the Amarna Letters, all the pieces fit together nicely. The biblical account of the Exodus is an historically reliable account of how the people of Israel escaped slavery in Egypt.

This post is also published at https://theologylighthouse.substack.com/p/archaeology-evidence-supporting-the

Comments

Post a Comment